A bit like porcini mushrooms emerging one fine morning from their underground matrix of mycelium – listen carefully, at this precise moment their hatching goes “plop!” – iron ore is found on the ground in Périgord. You have to imagine a labyrinth of ferruginous veins, carpeted under the mosses of the forest plateaus.

Back when Making Iron wasn’t Hell!

Grape harvesting, hay making, collecting iron and picking mushrooms… Chronicle of peasant life through the seasons and along the veins in the Périgord in the Middle Ages

From prehistoric times, the search for iron ore began in the heart of the forests, with at the time, it seems, a fascination for certain very hard slabs erected as monuments. We find in the Dordogne megaliths built in the Neolithic period, 8000 years ago, made up of thick, very ferruginous oxidized slabs.

In the Middle Ages, it was the peasants who searched for iron ore deposits on behalf of the Lord or the Abbot, in their spare time, between the end of the grape harvest and the hay harvest. This same lost time during which they prepare the coal with the local oaks and chestnut trees.

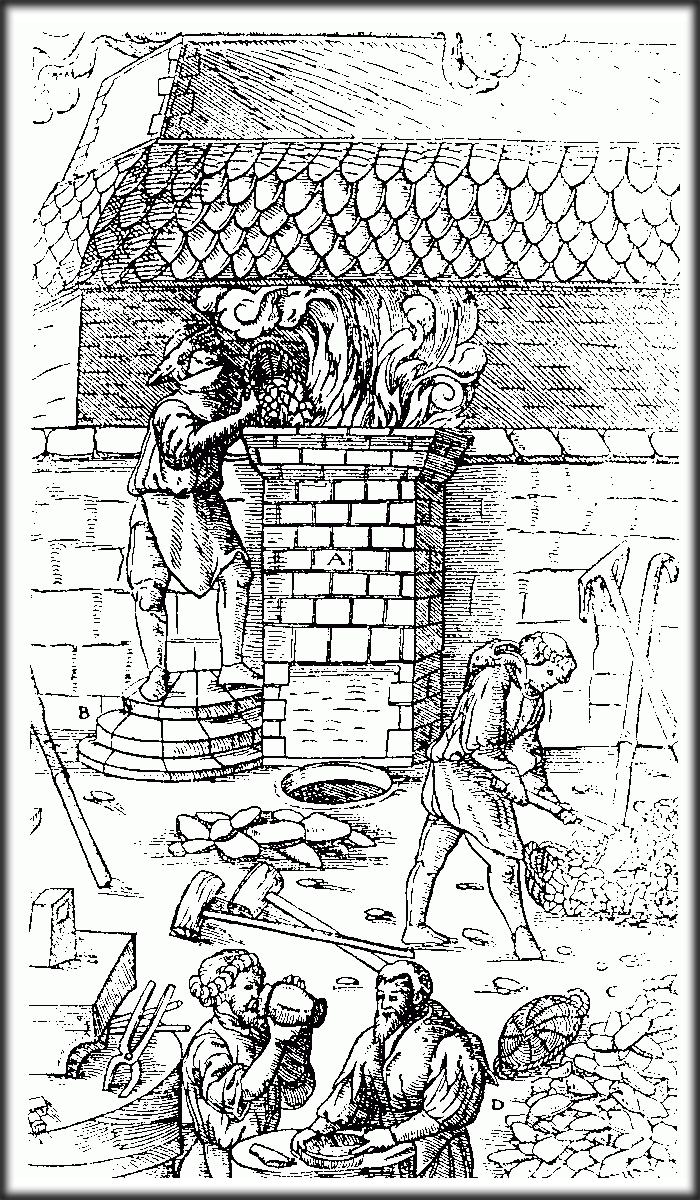

Once the seam has been excavated, a bloomery is built. It is a question of building on the ground a chimney flue in terracotta bricks, at the height of men. Five or six men in total place in this furnace made in the middle of the forest, near the surface metalliferous deposits which they have begun to exploit, hot coals then the ore extracted, washed and pounded. Waterskins filled with air ensure combustion thanks to entrances provided for this purpose, while the metal is vigorously stirred with the help of a green wooden pole.

The famous slags that can still be found today in our Dordogne forests is the trace of the location of these primitive furnaces.

This rudimentary metallurgy called « à la catalane » practiced during the High Middle Ages, allowed a direct reduction of iron ore. The mass obtained was immediately worked on the spot by the blacksmith. The quality of the local ore was good but the yield was limited, no more than 4 to 5 kilos of iron per casting.

As these peasants and charcoal burners needed to have close at hand both ore for iron and wood for charcoal, as soon as one or the other resource was exhausted, the bloomery was abandoned to make another one elsewhere.

This beginner metallurgy was thus itinerant, always finding new opportunities thanks to the many ferrous veins in pockets or in plates available under the forest cover itself generous in oaks and chestnuts particularly indicated to manufacture coal.

A little geological parenthesis. How did iron end up embedded in the form of slabs or ore pockets on the forest plateaus of the Dordogne?

Great ! A bit of geology to remind us that, like plants and animals, rocks are also alive and have been constantly evolving on Earth for 4.5 billion years.

Iron is found in Périgord in the form of various ferruginized alterites. Trapped in the karst network of limestone from the Upper Cretaceous – a period when dinosaurs swarmed on the horizon – these ferruginizations were formed by the addition of different proportions of iron and silica.

The result will be either veritable silico-ferruginous slabs enclosing the iron in the crystal lattice, or nodular cuirasses with a hematitic cortex with a high iron oxide content.

From itinerant forges to hydraulic forges, the rise of a metal industry in Périgord

Rich in these pockets of hematite and these hard slabs full of iron, the Périgord which extends from Nontron in the North West to the gates of Fumel in the South East, will become a very active region of iron ore extraction from 16th to 19th century. Three main metallurgical centers will prevail:

- that of Nontronnais, in the Bassin du Bandiat

- that of Excideuil-Hautefort, on the valleys of the Loue and the Auvézère

- that of Fumel-Cadouin in the south of the Périgord Noir, between the Lot and the Vézère.

In 1860 there were no less than forty forges and blast furnaces from one end of the Dordogne to the other, before the decline which would inevitably occur at the end of the 19th century due to the industrial revolution.

From traveling bloomeries in forests to hydraulic blast furnaces in the valleys, what happened?

We learn, we innovate and we always want more. This is what advances all forms of human industry to excess.

The secret to going from iron to cast iron is the temperature of the furnace.

Clearly, the bloomery transforms the ore into iron, the blast furnace transforms the ore into cast iron.

After the Hundred Years War, the thirst for rebuilding and fighting, because we never get tired of it, required a rise in metallurgical production.

The main objectives are:

- rebuild monuments

- strengthen the armament

- produce agricultural tools

- develop domestic comfort.

Basically, we need muskets and cannons, bells and hinges, pots and pans. And above all, large, very solid vats, at home for large laundry and in the Colonies, for extracting sugar from cane. These huge “vats” hitherto out of reach in terms of manufacture will experience a real boom in the 17th century.

Bloomeries built in the middle of the forest, it is exceeded. Furnaces and forges now have the hydraulic power of rivers. These are the mills that will allow a much better reduction of the ore and a much more powerful hammering of the iron burls.

Better still, thanks to a temperature which crosses the threshold of 1500°, the production of cast iron capable of being cast hot in clay molds will make it possible to produce all sizes of boilers, whether the soup is simmered there for an entire village, that we do the big spring bugade – laundry in Occitan – or that they are promised a long journey to the Colonies where these boilers of sugar will be eagerly awaited.

Some of these old vats, generous for soup, perfect for large washes or stackable to send them by boat to the Colonies, have managed to cross the centuries and come back among us.

Aux-Rois-Louis offers you some remarkable survivals, from the famous foundries of Périgord.

![Large cast iron vat for laundry Large cast iron vat for laundry – 16ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME076]](https://www.aux-rois-louis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ME076_P1660128.jpg)

![Sugar boiler for the Colonies – 16ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME075] Sugar boiler for the Colonies – 16ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME075]](https://www.aux-rois-louis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ME075_135.jpg)

![Small vat in cast iron for the soup Small vat for the soup in cast iron – 17ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME077]](https://www.aux-rois-louis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ME077_P1660136.jpg)

![Small vat for the soup in cast iron – 17ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME077]](https://www.aux-rois-louis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ME077_P1660136-1024x1024.jpg)

![Large cast iron vat for laundry – 16ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME076]](https://www.aux-rois-louis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ME076_P1660128-1024x1024.jpg)

![Sugar boiler for the Colonies – 16ᵗʰ century – Fonderies du Périgord – [ME075]](https://www.aux-rois-louis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ME075_135-1024x1024.jpg)